Alison Fragale kicked off BEx 2019 with an intriguing presentation titled Negotiation: The Swiss Army Knife of Relationship Management. The title alone suggests that, like a Swiss Army Knife, the negotiation skill-set is multi-purpose and can help us in many different situations. It also suggests that negotiation, used properly, can build relationships.

As leaders we negotiate and influence daily. Most of our work, tasks and results are accomplished through others. We also negotiate with our families, friends and communities outside of work. Therefore, it seems logical that our skills in negotiating are worth developing to be better leaders.

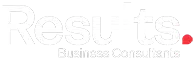

Many people see negotiation as an “us versus them” game. But great leaders understand that negotiation and influence is more akin to mutual problem solving. Most of our negotiations happen with people that we have ongoing, long-term relationships with (our peers, employees, families, etc.) where an “I win, you lose” approach will, over time, compromise the relationship. A mutual problem solving, or WIN:WIN, approach is foundational for leaders looking to create sustainable performance.

With that underlying principle in mind, Alison provided these tools in her Swiss Army Knife of Negotiating:

- Make a Start – many opportunities to improve never happen because people are reluctant to make a start. As human beings we may avoid the emotion or conflict of a high-stakes conversation, but a destination is never reached without at least beginning the journey.

- Aim High and Make the First Move – research supports that the opening offers or positions significantly impact the final outcome of any negotiation. Those transactions where an initial offer is high will almost always result in a final agreement that is better. Alison provided many examples of research into compensation negotiations and major purchase agreements to support this.

The best reaction to an initial offer from another party is an “interested no”. An outright no risks the other party walking away from the table completely (“this person is being unreasonable”), while an easily achieved “yes” indicates that there was probably room for a more favourable outcome, and so-called “money was left on the table”. Somewhere in between is the best reaction to an initial offer.

- Be Precise yet Flexible – when dealing with numbers, using precise values (e.g. $4275 vs. 4300) communicates that more thought or research has gone into coming up with the number and will be taken more seriously by the other party. At the same time, an attitude of flexibility communicated through multiple offers and tentative language suggests a willingness to discuss further. An example might be in a salary negotiation where an employee says, “the average for this type of role in our city is $56,427, with a range from $50,000 to $60,000.”

- Don’t Pick a Fight, Create New Value – Alison shared the story of the “Malice in Dallas” arm-wrestling match in 1992 between Herb Kelleher, Chairman of Southwest Airlines and Kurt Herwald of Stevens Aviation over a trademarked slogan. Instead of following a typical process of calling lawyers and getting embroiled in a legal battle, the companies used the squabble as an opportunity for creative problem solving which ultimately generated millions of dollars in free PR and recognition, as well as raising significant funds for charity. When negotiators move from combatants to mutual problem solvers, space is created for new ideas and unforeseen value.

- Focus on the Relationship as Much as the Transaction – as mentioned, many of the people we negotiate with in our leadership role are long-term relationships. We need to take the time to understand the needs and values of people behind their negotiating positions. This takes time and authentic curiosity to deeply understand what creates a winning outcome for all parties. This information can then surface new variables in a negotiation which are low cost to one party, but high value to the others.

As an example, Alison talked about the candy trading that goes on between her young children after Halloween each year, citing how one of her children uses Skittles, which she doesn’t like, as a valuable trading commodity with her sibling who does like them. Understanding the likes, wants and needs of the person you are negotiating with informs these strategies.

Many of these concepts are not new. I am reminded of the classic 1981 book by Fisher and Ury titled “Getting to Yes” which introduced concepts like “Focus on interests, not positions” and “Separate the people from the problem”. But Alison reinforced these foundations with updated research and a helpful framework to ensure more deliberate execution. When applied effectively, these strategies can multiply the performance of a leader and the organization.

What experiences have you had with these tools for effective negotiation? Please comment below.